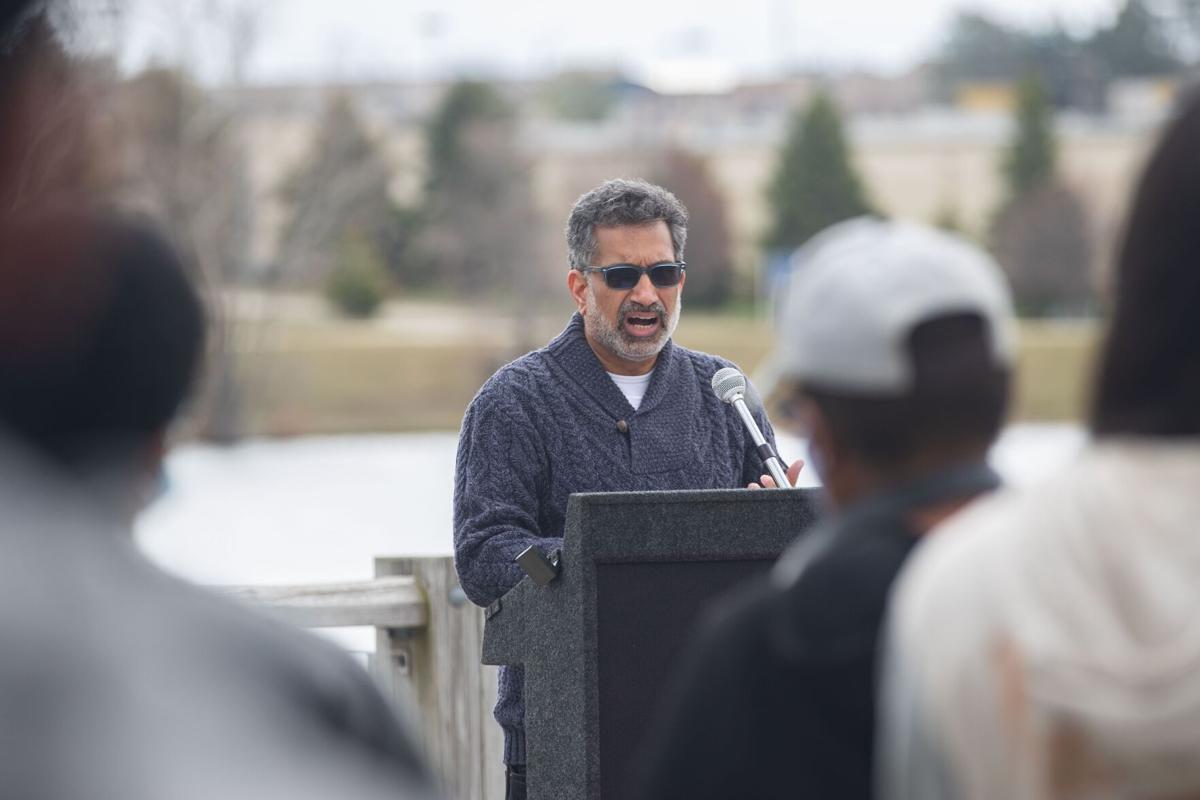

Dr. Ali Khan, a former assistant surgeon general and the third dean of the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health, has an impressive career spanning public health emergencies, global health security, and preparedness. With 23 years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), he directed the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, managing a $1.5 billion security program. He played pivotal roles in bioterrorism preparedness, responding to major crises like anthrax attacks, Ebola, and Hurricane Katrina, and advancing global health initiatives, including polio and guinea worm eradication. Dr. Khan is a champion for improving public health systems, integrating health data, and reducing health inequities.

I interviewed Dr. Khan back in 2018, but the conversation remained unpublished until today, several years later. While some of the details may now seem outdated, they still carry an eerie relevance—particularly since the interview took place before the 2019 Covid-19 pandemic. Dr. Khan’s predictions about a global pandemic, made seven years ago, now seem strikingly prophetic, and his insights about the ongoing threat of H5N1 Avian influenza are equally unsettling. His words serve as a stark reminder that our world may not be as safe as we think, emphasizing the critical importance of continuing to prioritize disease surveillance and resilience in public health efforts.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Do you think the world is in danger of experiencing another severe pandemic in the future?

ALI KHAN:

I believe it’s inevitable that we will have a severe pandemic in the future. In just the last 20 years, we’ve seen pandemics caused by influenza. We can expect more pandemics, especially from influenza. While the severity may vary, there's no reason to think we couldn’t see another influenza pandemic as severe as the 1918 one, even with advancements in medical therapeutics since then.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

I might be jumping ahead a bit, but people often argue that a similar pandemic to 1918 isn’t likely because of medical advances. But I always tell people that the world has changed a lot since then. Air travel is faster, there are more people, and diseases can spread much more quickly now. Do you think it’s still a realistic concern?

ALI KHAN:

There are two key points here. One is the potential for a pandemic. Influenza is a zoonotic pathogen that exists in wild birds, so it’s always out there in nature. These viruses can mutate rapidly, which means we could lose immunity to them. We know that viruses like these can be deadly, as we've seen with some bird flu viruses, although they haven’t spread widely in humans. But yes, they can be deadly, and they can spread quickly, especially with modern air travel.

The second point is the severity. The 2009 influenza pandemic was a global event, but it wasn’t as severe as 1918. Some people had some immunity, which made it less lethal, but it still spread widely. However, we won’t have a vaccine in the early stages of an outbreak, and it could be worsened by bacterial infections on top of the influenza infection. Even in a non-pandemic year, when flu seasons are particularly severe, our health systems become overwhelmed. So, during a full-blown pandemic, the situation could be even worse.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Thinking about other past outbreaks—Ebola, SARS, MERS, and now even measles—what kind of response do you think healthcare organizations, public health departments, and even local, state, and federal governments should have when it comes to preparedness?

ALI KHAN:

Without a doubt, they need to be working on new preparedness strategies. Let me back this up with some data: The National Health Preparedness Security Index rates us at 6.7 out of 10. We’ve made small improvements over the years, but that’s still not enough. If we want to be ready for an influenza pandemic, or any other major outbreak or even bioterrorism, we are still not adequately prepared.

While we might be a bit better prepared mentally now than we were during the bird flu scare, we still have a lot of work to do. There were more cross-agency collaborations during that time, and we laid the groundwork for those relationships. But in terms of actual preparedness, we have a lot to improve. State and local agencies, working with the CDC and Homeland Security, should reset and come up with new strategies to raise our preparedness rating to something closer to 8 or 9.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Given all the diseases we've discussed, do you think we can still apply lessons from historical pandemics—like the Black Death in the 14th century—to today’s public health infrastructure?

ALI KHAN:

The historical lessons don’t really change. We need to be able to recognize something unusual in our community, identify why it’s happening, and use that information to come up with prevention strategies. We also need to ensure we have medical countermeasures ready, or at least the infrastructure to create them. In some ways, science has made huge strides in areas like epidemiological investigations. We’re not blaming the Black Plague on demons anymore, for example. But there are still a lot of historical lessons that help guide how we should respond to an outbreak.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Do you think the hysteria around pandemics has changed during your 20 years in the field?

ALI KHAN:

Not really. For example, when we had just one case of Ebola imported into the United States, there was a media frenzy. Then, of course, we had two nurses who became infected, but thankfully, they both recovered. Even so, the media hysteria spread to the public, with people sending death threats to us here at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. They didn’t understand that we had them in a special bio-containment unit to protect both the patients and the healthcare workers. Yet, people were still terrified. The situation was completely safe for the community, but the fear was out of control.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

That’s a good segue into my next question. When we saw the H1N1 outbreak, we saw the whole spectrum of reactions—some people thought hospitals would fill up with dead bodies, while others thought we were just making it all up. So, when a real, severe pandemic strikes, what kind of physical, emotional, and sociological effects could it have on society?

ALI KHAN:

Let’s break it down. Emotionally, people might panic if they can’t get into healthcare facilities, especially if they think they have a severe infectious disease. If family members get sick or die unexpectedly, that fear will only increase. So, outbreaks have huge emotional and social impacts depending on how serious the disease is. It could also disrupt infrastructure. Think about cops, electricity workers, or people who keep water treatment plants running—if they get sick, it could cause significant disruption. If a large proportion of the workforce gets sick, critical infrastructure may collapse, and society will feel those effects.

“There's no reason to think we couldn’t see another influenza pandemic as severe as the 1918 one, even with advancements in medical therapeutics since then.”

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

One thing I always tell people is that it doesn’t take long for a grocery store to run out of supplies.

ALI KHAN:

Exactly!

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

If 10 to 15% of workers are out sick or staying home to care for family members, it doesn’t take long for things to start falling apart. I try to explain this to people, but sometimes they have a hard time imagining it happening in America. I point to case studies from other countries, but what would you tell skeptics who think our infrastructure couldn’t collapse, even temporarily?

ALI KHAN:

I’d ask them, "What happens during a hurricane, tornado, or snowstorm in your community?" We see infrastructure disruptions during those events all the time. Sometimes it’s physical damage to infrastructure, but often it’s just a shortage of people to keep things running. For example, in Georgia, when there’s a major snowstorm, the shelves are wiped clean because people are stocking up. The same thing happens with trucks bringing goods into the city—they stop if the people driving them are sick or scared. During SARS, people in places like Toronto, Singapore, and China were afraid to go out, which affected their economy and infrastructure. So, even in today’s world, public health threats can disrupt infrastructure, and that disruption would be much worse in a real pandemic.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Going back to 1918, what made that pandemic so dangerous at the time?

ALI KHAN:

It was a true pandemic. It spread rapidly across the world and had a higher lethality than typical seasonal flu outbreaks. What made it even more deadly was its impact on younger adults, unlike most flu outbreaks, which tend to be more dangerous for the very young and very old. This affected the general working population, making it much more lethal.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

A lot of people have tried to compare the 1918 pandemic with current events, and many believe that World War I helped spread it faster, along with a lack of education and the fact that they didn’t even know the virus existed. One question I want to ask is: How important is it to understand the nature of a disease—whether it's influenza, SARS, or something else—before we can take action to stop its spread or mitigate its effects?

ALI KHAN:

Whether we're aware of a disease or not doesn't stop it from spreading. For example, when the original SARS outbreak started, no one knew what SARS was, but it didn’t matter—the disease spread anyway. In the last 10-15 years, with the advent of air travel, diseases can spread worldwide very quickly.

Just because we’re not in a situation like 1918 doesn’t mean a pandemic can’t happen again. It could happen at any time. I'm concerned about diseases like SARS, MERS, and Zika, among others. Even with Zika, we knew what it was before it spread across the Americas. So, just because we don’t have a world war or something like the 1918 situation doesn't mean diseases can't spread rapidly, especially in the context of modern transportation.

The other thing to consider is prevention measures. Until we understand the disease, we can't implement effective prevention. For example, is it spread person to person, by contact, by food or water, or through blood or sexual transmission? You need to understand how it spreads before taking action. Prevention measures are crucial right from the start—you don’t need a vaccine to stop it from spreading. Hospitals can still manage these diseases without vaccines. Take SARS or MERS, for example—we don’t have vaccines for them, but we’ve been able to handle them. Once we understand the disease better, we can start working on vaccines, antivirals, and treatments.

“Even in today’s world, public health threats can disrupt infrastructure, and that disruption would be much worse in a real pandemic.”

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

A lot of people have heard of H5N1, but they don’t fully understand if there are other flu strains out there that could cause a pandemic. Can you talk about some of the strains the CDC is keeping an eye on?

ALI KHAN:

H5N1 wasn’t that long ago—about 13 or 14 years ago. There are over 16 different types of influenza viruses that we worry about. Many of them are maintained in waterfowl and have the potential to cause severe disease in humans, aside from H5N1. Right now, H7N9 is another strain we’re watching. But rather than focusing on the exact strain, what’s important is that these viruses are out there in animals, they can spread, and they have the potential to cause severe illness in humans.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

While we're on the topic, could you explain the difference between antigenic shift and antigenic drift?

ALI KHAN:

Sure! The influenza virus is made up of proteins on its surface that allow it to infect us. Each year, the virus changes slightly—this is called antigenic drift. These small changes mean the virus is different enough that the flu vaccine from last year might not protect you from this year’s strain. Sometimes, the virus undergoes a bigger change. This happens when it swaps genes with other animals or humans, and the outer coat of the virus changes dramatically. This is called antigenic shift. When this happens, people’s immune systems haven’t seen the new strain before, so it can be much more dangerous.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

That helps a lot, especially when people wonder why flu vaccines don’t seem to work sometimes. I get a lot of questions about that every year. I try to explain antigenic shift and drift, but it’s good to hear it from you.

ALI KHAN:

Exactly. The reason people need to get vaccinated every year is because the virus changes a little bit each time. The flu vaccine is updated to cover those changes. Even though the vaccine might not prevent you from getting sick, it can still help reduce the risk of serious complications like hospitalization or death. So even if you get sick, you might not get as sick as you would have without the vaccine.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Sometimes the success of public health isn’t visible because people aren’t getting sick. If we’re doing our job, people stay healthy and don’t notice it.

ALI KHAN:

Absolutely. We’re the invisible guardians of health in the community. When we do things right, people don’t get sick, and they don’t always realize the role we’re playing in preventing that.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

So as we look to future, avian or swine pandemics, they are obviously different from seasonal flu. Would they potentially tend to affect younger adults?

ALI KHAN:

Yes, like in 1918, the flu affected younger adults more than older ones. I think it’s still a bit speculative as to why that happened. Some theories suggest that younger adults’ immune systems were too strong, and that caused an overreaction that ultimately led to death. Others suggest that older adults may have had some protection from a similar virus they encountered earlier in life. But it’s hard to say for sure.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

I’ve seen a lot of theories out there, like that older adults were protected because they had seen a similar virus before. But then why didn’t the younger children die as much? There’s still a lot we don’t know.

ALI KHAN:

Exactly. It’s all still speculative. We don’t have a definitive answer, but it’s something we’re still trying to understand.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

So, looking at today’s world, what can the average person do to prepare for a potential pandemic, especially one that could overwhelm our healthcare system?

ALI KHAN:

I have two key messages. First, personal preparedness: Are people vaccinated? Are they taking care of their health? Do they have enough supplies at home, like food and water, in case of a disruption? Do they have a plan for how to contact family members?

Second, get involved in the community. Instead of just thinking about surviving, how can people contribute as responders? Have they taken a CPR course? Are they part of a local disaster medical team or civil response team? It's crucial to be engaged with your community to help build resilience. This includes checking in on neighbors, participating in local volunteer efforts, or being active in your church or other community activities.

Of course, it’s also good to be prepared with food and water for a few days, but there’s a lot more people can do to be part of the solution.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

I'm so glad you mentioned community involvement. It’s such an important part of preparedness.

ALI KHAN:

I couldn't agree more. We don’t fully understand how community resilience works or how to strengthen it, but we do know it’s essential for responding to and recovering from outbreaks. Resilient communities do better overall.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

Shifting focus a bit, if you could make changes to improve the healthcare system to be better prepared for a pandemic, what would those changes look like?

ALI KHAN:

When you look at our national Public Health Preparedness Index, healthcare preparedness is the lowest of all the domains. The second lowest is community resilience. The healthcare system is a massive, $3.4 trillion industry, and it’s been a tough nut to crack because so much of it is siloed and privatized. There’s not great communication or a strong focus on preparedness.

A positive step is the new CMS laws that require healthcare entities to have preparedness plans. Once that’s fully implemented, it will be a good start. But that’s just the beginning. What we really need is a system that engages all healthcare entities within a community to respond together. We tend to think about hospitals, but what about doctor’s offices, urgent care clinics, and nursing homes? We need to think holistically about healthcare. What about EMS? We need to plan for healthcare preparedness at the community level, where all these different actors work together.

For example, we should know how emergency rooms are distributed across a community, not just in one hospital, so we can respond better to an outbreak. Often, you don’t need to go to the hospital; in fact, you should probably stay out of the hospital. How do we communicate that to the public? Right now, EMS workers are required to take patients to the hospital even when they don’t need care. EMS should be part of the healthcare system, and we need to figure out how they can triage more effectively during a pandemic. Ultimately, it will take holistic, community-level preparedness at the system level.

DISASTER INITIATIVES:

I think that would go a long way in National preparedness. Do you have any final thoughts?

ALI KHAN:

I think it’s good to make the point that while pandemics are inevitable, the consequences aren’t. We have the ability to mitigate the impact of a pandemic with good foresight and solid preparedness. But that requires resources and commitment, which aren’t always guaranteed.

The 4-11

Though this interview was recorded years ago, its warning remains as relevant as ever. Disease outbreaks, as long as our world exists, will always be a threat to our security. While the Covid-19 pandemic was significant, it also exposed a darker side of our society. Regardless of their scale, disease outbreaks are amplified when political agendas dominate our response. They are not influenced by political ideologies—they simply exist, and it is this simplicity that makes their potential for destruction so terrifying. The Covid-19 pandemic was the most severe we’ve seen in the last century, but it won’t be the last. We cannot rule out the possibility that the next outbreak may be even worse and arrive sooner than we expect. Dr. Khan’s advice remains practical and sound, reminding us that we must stay vigilant, support rational efforts to minimize the impact of future pandemics, and work together when they arise.

Dr. Ali Khan, a former assistant surgeon general and third dean of the University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Public Health, has had a distinguished career in public health, focusing on global health security and preparedness. With 23 years at the CDC, he led major public health initiatives, including bioterrorism preparedness, crisis response, and global health programs like polio and guinea worm eradication, while advocating for improved health systems and reduced health inequities.

Follow Dr. Khan on X

About the Author

Mark Linderman is the owner of Disaster Initiatives, an online company that provides communication leaders with the tools needed to address their communities and the media throughout a crisis, and teaches the communicator to approach crisis communication from the listener’s perspective. He is a Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) and nineteen-year veteran of Public Health. He instructs Crisis & Risk Communication within the field of disaster preparedness for seven universities, including Indiana University’s Fairbanks School of Public Health. Mark is considered a Subject Matter Expert in the field of disaster-based communication and is a widely received public speaker and advocate for disaster preparedness.

Mark Linderman,

MSM, CEM, CCPH, CSSSS

Visit DISASTER INITIATIVES for more information.