Surviving one major pandemic wasn’t enough—now there’s already chatter about the next one. While history tells us that severe pandemics tend to strike roughly every hundred years, that doesn't mean we can predict exactly when or how bad the next one will be. But it’s clear that it's just a matter of time. Most pandemic preparedness plans are rooted in the most infamous of all: the 1918 Spanish Flu, which claimed up to 100 million lives worldwide. To help us grasp the full scale of what we're up against and how we can better prepare, we sat down with pandemic expert and bestselling author John Barry. John’s deep expertise in public health policy has led him to work with a range of organizations—from local to international—on risk communication and preparedness. His 2004 book, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, was named the year’s top science book by the National Academies of Science. In this interview, John Barry reflects on the lessons from the 1918 pandemic and how they still apply to the world we live in today.

DISASTER INITIATIVES: Given the terrifying potential of bird flu strains like H5N1 and H7N9, with case fatality rates as high as 60%, what would happen if these viruses evolved to spread more easily between people? Could we be facing a scenario worse than the 1918 Spanish Flu, and how prepared are we for such a pandemic today?

JOHN BERRY: I remember when Tom Frieden, former head of the CDC, spoke to The Washington Post after he left his position. The reporter asked him what kept him up at night. His answer? Influenza. He made a point to say that influenza is always the worst-case scenario, and he’s not wrong. The 1918 Spanish Flu wasn’t the only terrifying pandemic we’ve had and it was definitely one of the worst. Fast forward to today, and we’ve got two particularly nasty strains of bird flu, H5N1 and H7N9, floating around. The scariest part? These viruses have a case mortality rate of about 50-60%. And that’s with patients who are getting top-notch care in an ICU.

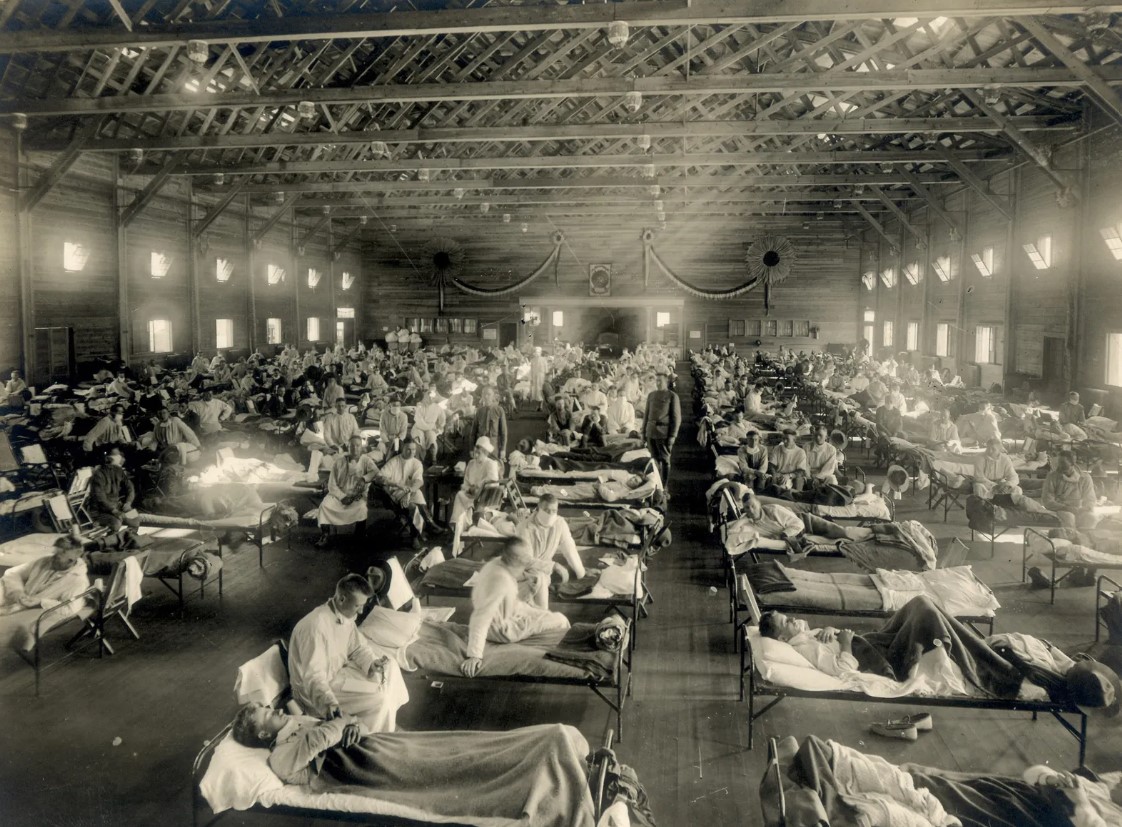

But let’s be real: if we faced a pandemic, the hospital ICUs would be packed in just a few hours. And the medical staff? They’d be reduced by at least 20%—and that’s if we're lucky. The rest would be out sick themselves. So, you can see how quickly things could spiral, and the case mortality rate could climb even higher.

It’s pretty chilling, honestly. But here’s the kicker: the reason these viruses are so deadly right now is that they attack cells deep in the lungs. So, if you catch it, you're pretty much starting off with viral pneumonia. The good news, though? That’s also why they don’t spread easily between people. The viruses are only binding to cells deep down in the lungs, not in the upper respiratory tract where it could spread through sneezing or coughing.

Now, if these viruses somehow evolved to latch onto cells higher up in the respiratory system, we’d be looking at a whole different scenario. That’s when it could truly become a pandemic virus. And the case fatality rate? It would probably drop dramatically. Would it be as bad as 1918? Maybe not. Worse? Hard to say.

DISASTER INITIATIVES: What if a bird flu virus like H5N1 mutates or reassorts in a way that allows it to spread easily between humans—could we see a repeat of the deadly 1918 flu, but with even more devastating consequences? And with the rise of mixing bowls like pigs, how close are we to facing a pandemic virus that our immune systems have never encountered before?

JOHN BARRY: That’s a really good question, and honestly, I don’t think anyone has the perfect answer. What we do know is that pandemics tend to change the game in unexpected ways. Take the 1918 flu, for example. Over 90% of the people who died were under 65, which is pretty crazy. It’s the opposite of what we usually see with seasonal flu, where the elderly are more vulnerable.

Now, you’re asking about the difference between seasonal flu and a pandemic virus, and there’s a pretty big one. With seasonal flu, the virus changes a bit each year, so we need a new vaccine every time. This is because of something called antigenic drift, where the virus's surface proteins keep evolving. Your immune system has some protection because it's seen those changes before, even if it’s not the exact same virus each year.

But with a pandemic, things are a lot more intense. The virus can go through something called antigenic shift, which means it introduces an entirely new surface protein that your immune system has never seen before. That makes the population much more vulnerable because we don’t have any immune protection, so the virus spreads way faster and more widely.

Here’s where it gets even more interesting: all flu viruses originally come from birds. Birds are the natural hosts, and over thousands of years, this virus has jumped species, affecting all sorts of animals. The 1918 flu, for instance, even infected seals, tigers, dogs, and even cows. In fact, humans probably passed the virus to pigs, not the other way around.

So, there are two main ways the virus can jump species. First, the bird flu virus can mutate in a way that allows it to bind to human cells. That’s how we got H5N1, for example. Before that, scientists didn’t think it was possible for a bird flu to directly infect humans, but now we know it can happen.

The other way is through reassortment, which is a fancy term for swapping genetic material. If two different flu viruses infect the same cell, they can mix their genes—kind of like shuffling two decks of cards together. When that happens, a brand-new virus is created. And guess who’s got the perfect environment for this to happen? Pigs. They can host both human and bird flu viruses at the same time, so they’re kind of like a “mixing bowl” for new viruses.

DISASTER INITIATIVES: Could a new flu virus jump directly from birds to humans, spreading faster than we’re ready for? And could hidden immunity from a similar virus in the past explain why so few people over 65 died in the 1918 flu?

JOHN BARRY: So, this is where things get interesting. Pigs have been called a “mixing bowl” because they can host both human and bird flu viruses at the same time. It used to be thought that a flu virus had to go through a pig—or some other mammal—before it could jump to humans and cause a pandemic. But we’ve learned that’s not true anymore. We now know that a virus can just go straight from birds to humans.

When a virus comes along with completely new antigens—things your immune system has never seen before—most people have zero natural protection against it. A few lucky people might have some immunity based on past exposures, but for the vast majority of us? We're wide open. That’s why a new virus spreads so fast.

Now, here’s a crazy idea: there’s a theory about the 1918 flu that might explain why so few people over 65 died from it. The idea is that people who were younger—especially those under 65—might have been exposed to a similar virus when they were kids. But back then, it wasn’t deadly. It didn’t make the headlines or cause massive death, but it was enough like the 1918 virus that their immune systems had some built-in protection when the pandemic hit.

“The 1918 Spanish Flu wasn’t the only terrifying pandemic we’ve had, but it was definitely one of the worst.”

DISASTER INITIATIVES: With past outbreaks like H1N1, Ebola, and SARS teaching us hard lessons, could the world be better prepared for the next pandemic, or are we still just as vulnerable—especially considering the early panic around H5N1?

JOHN BARRY: We really need to take a close look at the disease outbreaks happening today—whether it’s H1N1, Ebola, SARS, or others—and see what lessons we can learn from them for future pandemics. When the book came out, H5N1 was starting to spread widely for the first time, and people were really scared about the potential for a pandemic. There were tons of meetings and governments around the world were scrambling to figure out what to do. I even got involved in some of those discussions, trying to figure out the best course of action.

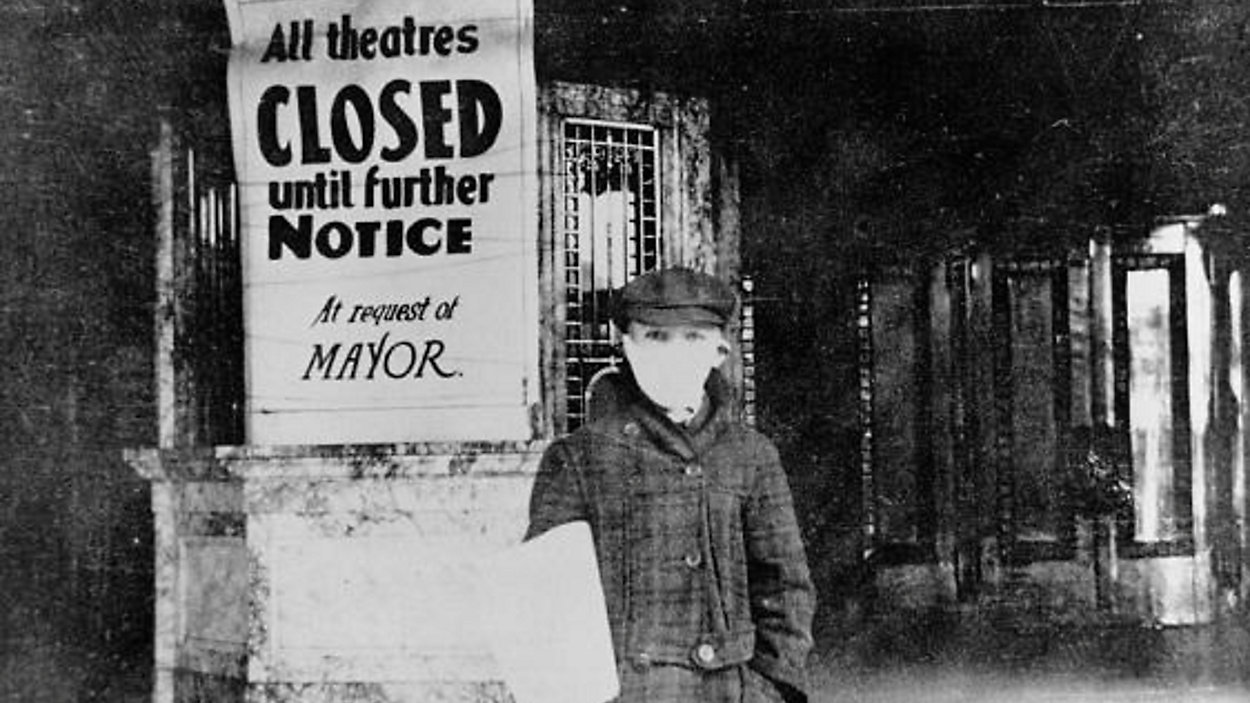

DISASTER INITIATIVES: With social distancing recommendations on the table for future pandemics, how effective can these measures really be in controlling the spread—especially when there’s doubt about whether they’ll work as well as some experts think?

JOHN BARRY: Our governments came up with a bunch of recommendations, most of which fall under the category of social distancing. Pretty straightforward, really. Honestly, I’m not as confident that those measures would work as well as some of the others in the room. I think they’re worth trying, and I’m definitely on board with them, but I do wonder if they’ll be as effective as some people think they will be.

DISASTER INITIATIVES: If strict quarantines didn’t even work during the 1918 flu on military bases, how realistic is it to think we could fully isolate and prevent the spread of a disease in today’s world without causing massive disruption?

JOHN BARRY: So, pretty much anything that keeps you away from others is going to help prevent the spread of infectious diseases. With flu, for example, most of it spreads through the air, but that doesn’t mean things like washing your hands won’t help. If someone coughs and touches a door, and then you come along and touch the same door half an hour later, you could pick up the virus—especially if you rub your eyes or touch your face afterward. But if you wash your hands first, that pretty much prevents you from getting it.

That said, it’s really hard to avoid getting sick entirely unless you lock yourself away from the world completely. Quarantine and isolation can help, but unless you’re doing it perfectly, it’s not going to stop the disease. The Army actually tested this out in 1918. They had 120 camps with thousands of soldiers, and in 99 of them, they enforced quarantines, while 21 didn’t. Guess what? There was no difference in how many soldiers got sick, even in the camps with strict quarantine measures.

The guy who did that study was a well-known epidemiologist named George Silver. He later became the first director of the American Cancer Institute. He did both a qualitative and quantitative analysis and found that the camps with strict quarantines had some effect, but it wasn’t huge. So, if you couldn’t successfully quarantine a military base during a war, the idea of isolating civilians in peacetime is pretty unrealistic. It would be disruptive and wouldn’t really change much.

DISASTER INITIATIVES: If we’d allocated more resources to tackling the flu instead of less deadly diseases, how much further could we have advanced public health measures like vaccines and prevention?

JOHN BARRY: So, the top priority here is developing a vaccine—a "universal" one that could protect against most flu viruses, or at least a lot of them. And guess what? We’re finally starting to put some serious money into that research. The dream is to have a vaccine that doesn’t require a new shot every year, one that’s more effective and could even protect us from potential pandemic strains. The good news is that scientists are actually feeling pretty optimistic about getting there eventually, with the research making solid progress.

But here’s the kicker: if we were making smarter, more rational decisions about how we spend our healthcare research dollars, we might already have that vaccine. Instead, take the CDC’s numbers on influenza. Since World War II, flu has killed anywhere from 3,000 to 80,000 Americans a year—the 80,000 was just last year (2017-18), which was the worst we’ve seen in a while. That’s a lot of lives lost. Now, think about West Nile—it's never killed more than 300 people in a year, and often it’s way less. But before H5N1 made headlines and got people worried, we were actually spending more money researching West Nile than we were on influenza. Makes you wonder, right?

“It’s really hard to avoid getting sick entirely unless you lock yourself away from the world completely. Quarantine and isolation can help, but unless you’re doing it perfectly, it’s not going to stop the disease.”

DISASTER INITIATIVES: Why do you think public health funding and attention can sometimes be swayed more by fear and media hype, like with West Nile, than by the actual threat of something like the flu that we deal with every year?

JOHN BARRY: It’s just how Congress operates sometimes. With West Nile, I used to joke about it, saying it was as if it came from some far-off place like Missouri or something. But honestly, if it weren’t for the fact that it came from Africa, it would’ve never gotten the attention or funding it did. People were freaked out, thinking it was some major threat, but let’s be real—it was never going to be a serious danger to human health. If you’re a horse, sure, it’s pretty dangerous, but for humans? Not so much.

I had a close friend who got infected and was really sick with West Nile Virus—almost didn’t make it—it’s still not something that should have caused that much panic. The numbers just don’t back up the hype.

Meanwhile, influenza, something we’ve all been dealing with for ages, just never seemed to get the focus or research funding it deserved. But now, it’s finally getting the attention and resources it needs, and thankfully, there’s a lot of progress being made.

The 4-11

We’ve already faced one major pandemic, and now there’s talk of another one looming on the horizon. History shows that pandemics tend to strike about every century. But that doesn’t mean we can just sit back and wait for the next one to arrive. The truth is, we can’t predict when it will hit or how severe it will be, but it’s likely only a matter of time. A lot of the plans we rely on today for handling pandemics are based on the 1918 Spanish Flu, one of the deadliest outbreaks in history, killing up to 100 million people worldwide. While Covid-19 was undeniably severe, experts like John Barry warn that even worse outbreaks could be on the way. The real question is: what will we do with the lessons we’ve learned from both Covid-19 and the Spanish Flu? How we respond now will shape how the world handles the next global health crisis. Will we rise to the challenge, or will we repeat the mistakes history might judge us for?

About John Berry

About the Author

Mark Linderman is the owner of Disaster Initiatives, an online company that provides communication leaders with the tools needed to address their communities and the media throughout a crisis, and teaches the communicator to approach crisis communication from the listener’s perspective. He is a Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) and nineteen-year veteran of Public Health. He instructs Crisis & Risk Communication within the field of disaster preparedness for seven universities, including Indiana University’s Fairbanks School of Public Health. Mark is considered a Subject Matter Expert in the field of disaster-based communication and is a widely received public speaker and advocate for disaster preparedness.

Mark Linderman,

MSM, CEM, CCPH, CSSSS

Visit DISASTER INITIATIVES for more information.